IN THE MIDST OF THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

LIVING, READING, PAINTING IN NYC

Saturday, November 21, 2020

I read a book recently, The Inner Game of Tennis by W. Timothy Gallwey, that I wish I had read while I was still teaching. The book was published 30 years ago, is still in print, and has sold close to a million copies. It is only superficially about tennis.

Gallwey’s theory is that we are each made up of two people, one guided by the brain (the ego-driven self) that has internalized all the things we are told growing up, and the other, guided by the body (the inner self) that has its own inherent needs, its own demands and requirements. It is this inner self that should be guiding us through life, but socialization and education tend to fight against it. The inner self, Gallwey believes, is endowed with an instinct to fulfill its nature: it wants to enjoy, learn, understand, appreciate, express itself, rest, be healthy, survive, and be what it is in order to make its unique contribution in the world. This self comes with a constant gentle urging; the person who works in concert with his/her inner self will be attended by a certain type of contentment.

Gallwey writes that the first rule of successful living is recognizing that this inner self has all the gifts and capabilities with which we hope to accomplish anything, and it has its own requirements to live in balance with itself. To be able to listen to this self you have to let go of all good/bad judgments (of ourselves and others). Ultimately you want to be someone who is able to let go of anything — if necessary — and still be okay. Gallwey says we need to give priority to the demands of the inner-self in relation to all the external pressures from the ego-driven self.

Gallwey arrived at this philosophy through teaching tennis. He discovered that his students learned better if — instead of telling them what to do — he simply demonstrated actions, which allowed the students to by-pass, and not be distracted by his verbal instructions. This allowed the student’s body intelligence to kick in and emulate the demonstrated movements. Gallwey also says that there is no one right way to do anything in tennis; each person should be allowed to find his/her own way based on the uniqueness of their bodies.

I stumbled on this exact same notion teaching art which, like tennis, is a physical activity. I urged students stop thinking and simply allow themselves to try different things, a process that allowed their embodied intelligence to take over. I liked to refer students to the way they doodled, since doodling is an automatic, mindless activity guided by the hand, and relies on comfortable and natural gestures.

In 1974 when Gallwey wrote The Inner Game of Tennis, Zen Buddhism was not as prominent or as pervasive in American culture as it is today; reading Gallwey’s writing the philosophical parallels between his thinking and that of the American version of Zen Buddhism is inescapable. Both philosophies are founded on the belief that attachment to outcomes is what trips us up: as he said, “the aim is to be able to let go of anything — if necessary — and still be okay.” Gallwey extends the principles of his thinking to all activities, whereas when I was teaching, I thought these principles applied only to art making.

Gallwey and I both believe that, each person is actually born right and perfect for who he/she is, and that simply allowing ourselves to follow our innate sense, the one we come into the world with (placing this guidance ahead of what society and education tells us) we can realize our potential, and fulfill our destinies. To put it more succinctly, I believe what Miles Davis said, “The genius is the guy who is most himself.”

Wednesday, November 11, 2020

When I was in college a friend said she didn’t know what she wanted to do in life. I suggested she try figuring it out through a process of elimination by making a list of what she doesn’t want. She liked the idea but was troubled that she had to resort to using such a backdoor-way of finding out something so important to her.

It did seem like the majority of my students didn’t know what they wanted to do in life. I assured them that life is circumstantial, and they would find the right path more or less by stumbling across it. My students, being art majors, were in a particular quandary because even if they knew they wanted to pursue an artist’s life they needed to figure out day jobs to maintain themselves. Professions in the arts and liberal arts do not come with a directed path the way medicine, law, or accounting does.

In truth I think the majority of people find it hard to “figure out” what they want to do, in part because the brain isn’t the right organ to consult — or I should say — the brain is probably good at figuring it out if your path is straightforward — like —”I think I’ll go to Law School,” but not so good if your options are wide open. It’s no wonder that for multiple millennia young people tended to follow professionally in their parents’ footsteps. First because they had a way in, they had a sense of what was involved in that line of work, i.e., if it was farming, they grew up on a farm doing farm work. In those days it was probably easier to figure out that you didn’t want to enter your father or mother’s trade— to be a coal miner, a grocery clerk, a seamstress, a washerwoman, a milliner, a clergyman, a financier, or whatever.

But in our day, white collar jobs don’t involve working with your hands or using your body; they are usually some form of office work, and what exactly people do in offices is pretty opaque.

Why is it so hard to think through what path you should take in life? I think part of it is that school learning does not teach you to value or possibly even recognize the skills you have. Students have a very narrow way of viewing their skills, for example, they invariably overlook their personal skills — being organized, being outgoing, being good with people, being efficient, being good with money, being able to do public speaking, having patience, having an eye for detail, being able to organize people. Whether you succeed at a job relies at least as much on these personality qualities.

An artist friend of mine, Carmen Lizardo, tells an amazing story. She was born and raised in the Dominican Republic and came to the U.S. after high school. Before applying to college, she went to the Brooklyn Library and took an aptitude test. Her results came out: artist, artist, artist. Carmen knew nothing about art; curious, she went to the Metropolitan Museum of Art — the first art museum she ever entered — and she knew immediately that this was the world she wanted to inhabit. Indeed, she has turned out to be a wonderful artist.

I would love to get my hands on the aptitude test she took. It seems like every kid in school would benefit from taking such a test.

Saturday, September 26, 2020

A gripe I have with the public education system is its misguided reverence for book learning over hands-on learning. Book learning treats students as if everything important about them exists only from their neck up.

Embodied learning is at least as important, if not more so, than intellectual learning. There are two distinct ways of learning —academic learning that feeds information directly to the brain, and embodied learning which is used to acquire physical skills. Athletics and visual and performing arts are generally taught in gyms or playing fields, in art studios, and in conservatories.

A toddler does not learn to crawl or walk by being told how to crawl or walk. A toddler learns to crawl or walk by crawling or walking, just as a singer learns to sing by singing. Embodied learning is a more complex, more holistic route to knowledge, one that is less directed by the brain, more directed by the body. The two paths to learning are fundamentally different. Book learning is verbal, logical, and slow; embodied learning by-passes the logical brain and coordinates instinct, intuition and the body.

One example is the basic mammalian instinct to suckle: a kitten or a baby does not have to be taught to suckle. Locomotion is also instinctual — a baby abandoned in the wild, if she survives, will not remain on her back. By herself she will learn to turn over, crawl, walk, and run. We are born with these types of instincts — something we knew to do before we developed language. In this way we can say embodied learning is a more fundamental route to knowledge than verbal or textual learning.

This is not a topic I might have given much thought to had I not taught studio art for three decades. As an experienced teacher, I found myself constantly advising my students to “Stop thinking!” — explaining that their minds cannot solve whatever problems they were facing with their artwork — that only by doing, by trying things out physically would they find a way forward. This was news to them: a lifetime of education had taught them to value their thinking above all else.

According to Wallace Stevens, unlike the body, the brain is never satisfied. If we eat our fill, we stop being hungry, after a good night’s sleep, we feel rested and energetic. This is not the case with the brain: our brains know no limits; it constantly wants more. Our brains also lie. I subscribe to the edict “Don’t trust everything you think.” The brain is not to be trusted. But when we feel pain, have an upset stomach, or run a fever, we know it’s true: the body doesn’t lie, nor does it get caught up in fantasies, entertain illusions of grandeur, or do any of the other suspect things that our brains are constantly doing.

I will elaborate on this topic in the next posting. In the meantime, I leave you with this factoid: A Silicon Valley executive once said that he will not hire computer programmers who have never worked with their hands; he claimed that people who have failed to acquire hand skills cannot think in certain ways. (You know what they say: muscles that are not used atrophy.)

Wednesday, September 16, 2020

I have fallen well short of the goal I had when I started this blog of posting once a week. I’ve been feeling like I don’t have that much to say. I considered giving up the whole thing, but recently I figured out there is something I can talk about almost endlessly, since I’ve been doing it for the last 30 years, week after week, in my role as a college painting and drawing professor.

To teach well you need to break topics down into components, or graduated steps that students can follow. When I started teaching I noticed there were things I could do, yet could not explain how I did them; I noticed I operated on a series of (almost) subconscious assumptions that needed to be closely examined; and I noticed teaching exercised skills that I had but had no occasion to use in my normal life. Ultimately teaching grew very rewarding for me because it employed many more of my capabilities than I had ever had opportunity to use before.

Recently I sat down, and in five minutes, came up with a list of a dozen topics I could write about. They included:

- Cerebral learning vs. embodied learning

- The advantages of painting and drawing in being immediate and extremely flexible mediums

- What “process art” is about

- The counter-intuitive fact that 2-D painting and drawing mediums have surpassing capabilities to evoke space compared to 3-D mediums, including film and installation

- The difference between narrative and non-narrative art

- The difference between using symbols vs. inference in art

- The basic difference between believing your body vs. believing your brain

- The argument against an academic art education

- The importance of Formalism as taught by the Bauhaus

- The particularity of individual color sense

- Why I distrust Theory (capitalization mine)

- Why my students thought I could read their minds

- The importance of visual thinking — focusing on Einstein as an example. (Admittedly I would have to do a fair amount of research to carry out this topic.)

I promise to cover each of these topics, in no particular order, in upcoming blog postings. But I revoke my promise to post once a week. I think once every three weeks is a more realistic goal.

Wednesday, August 19, 2020

My friend, Janet Zweig, sent me a link to a July 29, 2020 New York Times Magazine feature about swifts, birds that are known to stay airborne for as long as ten months at a stretch. It was written by Helen Macdonald, author of the memoir, H Is for Hawk. The article is so beautifully written it is almost transcendent, and does absolute justice to the subject, an otherworldly creature.

According to Wikipedia, swifts belong to the same family as hummingbirds and share the unique ability to rotate their wings from the base. Swifts and swallows look similar, but according to singita.com swifts are usually black and white or grey in color whereas swallows often have a russet color on their heads, throats, or rumps. Swallows can also be distinguished by an iridescent blue that appears on their wings and backs.

Swift in flight.

Swift in flight.

Swallow in flight.

Swallow in flight.

Swedish researcher Susanne Akesson, said in National Geographic, “They feed in the air, they mate in the air, they get nest material in the air.” Because their wings are so long and their legs so short, “they can land on nest boxes, branches, or houses,” but due to their built they can’t really land on the ground, nor are they able to take off from a flat surface.

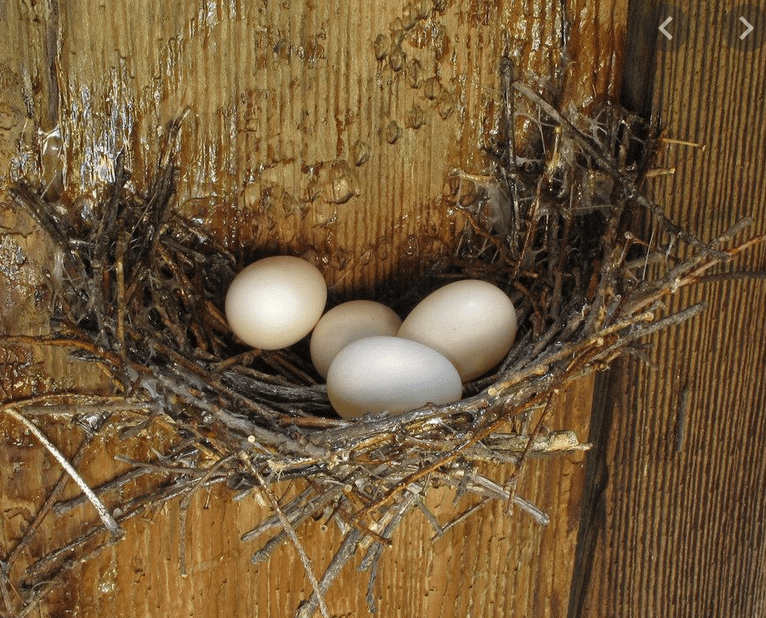

Their nests, which they like to build in obscure, dark and hard to reach places, are bonded together and attached to vertical surfaces with their saliva. The nests can be found in building hollows — under tiles, in gaps between windowsills, under eaves, and within gables.

Two swift nests attached to wood surfaces.

Two swift nests attached to wood surfaces.

Swifts mate for life, and they are long-lived. They start to breed at the age of four and typically live another four to six years. One swift was documented to live to the age of twenty-one.

Except during breeding season swifts tend to not land at all. They may have adapted their habits to match their feeding needs: their main source of food is high altitude insects: when hunting they store the insects in a special pouch at the back of their throats. The food is bound into a ball with their saliva; they may bring it back to their nests, or save to eat later. Once their broods are tipped out of the nest, the swifts never return. They travel in groups and can ascend as high as 10,000 feet. They fly so high they can orient themselves visually by looking down.

Chimney swifts.

Chimney swifts.

According to Wikipedia, “They often form ‘screaming parties’ during summer evenings, when 10–20 swifts will gather in flight around their nesting area, calling out and being answered by nesting swifts. Larger ‘screaming parties’ are formed at higher altitudes, especially late in the breeding season.

White-throated swift.

White-throated swift.

Swifts make massive ascents each day, once at dawn, and once at dusk. One researcher speculated that maybe “this is when they sleep… they take power naps by gliding on the way down.” [newscientist.com]

A swift was recently recorded to be flying at the speed of 69.3 mph. “And in a recent study, one of the tagged birds soared 40 miles without a wing-flap.” [Merrit Kennedy]

Swifts come in a range of sizes from the pygmy swiftlet that weighs less than an ounce, to the purple needletail that weighs 6.5 oz. The common swift weighs about 1.3 oz.

This is the link to the Helen Macdonald article, (https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/29/magazine/vesper-flights.html)

Friday, July 31, 2020,

Last month I listened to an audiobook by an astrophysicist, Max Tegmark, called Our Mathematical Universe, that I can’t get out of my mind. People say we are living in the Golden Age of Space Exploration, but I personally have not been paying much attention. This book, however, is so well written and accessible, it is like a primer for the uninitiated.

Did you know that space is infinite? Max Tegmark says that it is. I find this almost unimaginable — how can anything be infinite? And this infinite space is currently expanding, in the sense that things are moving farther and farther apart. Scientists document this by looking into space, which is the same as looking into the past. Things are so far away it can take millions of years for the light to reach us. The measure between forms decreases the farther away it is, and this increase of distance as it gets closer to us records the expansion of the cosmos.

The creation of everything that now exists happened about 13.7 billion years ago when the Big Bang occurred. We think of the Big Bang as the start of everything, but Tegmark, cautions that the Big Bang, instead of being the beginning of everything, may actually have been the end of something.

Did you know that 85% of the matter in this infinite space consists of dark matter? Dark matter isn’t dark — it’s invisible, and passes through everything, even us. Dark matter cannot be found within the electromagnetic spectrum (EM)]. EM radiation is energy that travels and spread out as it goes; the lamp by your bed side or radio waves are examples of EM radiation. Dark matter does, however, have mass: it accounts for about a quarter of the mass in existence. Scientists study dark matter by looking at the effects it has on visible objects. Dark matter and dark energy are the yin and yang of the cosmos. Dark matter causes attraction (through gravity) and dark energy produces a repulsive force (anti-gravity — it is the force that is making the cosmos expand over time). The visible world, that is, matter that we can see, accounts for only about 5% of the matter in space.

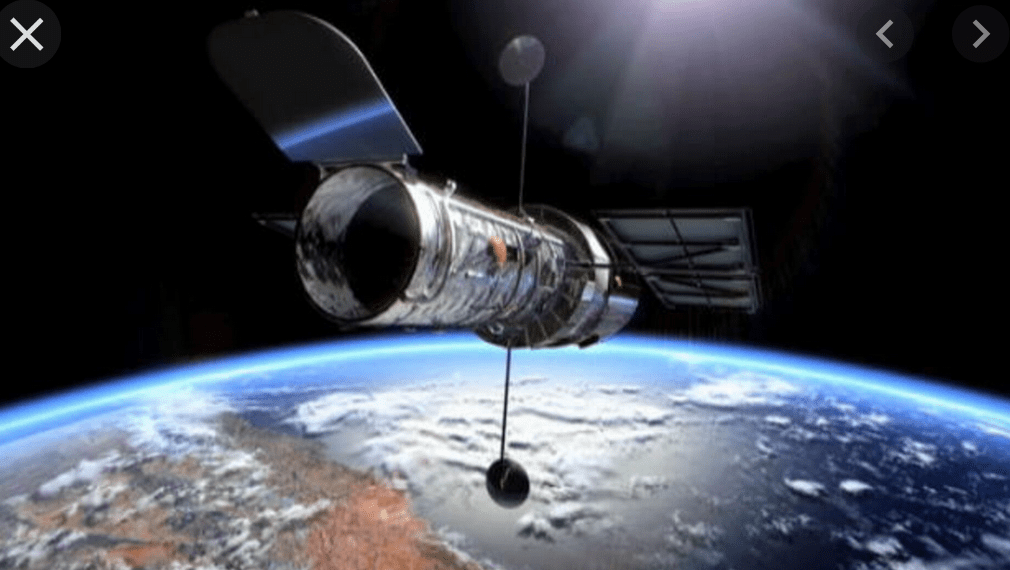

Much of what we know has been discovered through the Hubble space telescope. This is an image of the Hubble telescope. And the two images below were taken from it.

This is apparently a quasar, which are ultra-bright cores of distant active galaxies. An outflow like this one from a quasar functions like a tsunami in space, wreaking havoc within its galaxy.

This is apparently a black hole. Who knew black holes were so beautiful?

I followed along with the book pretty well until about half-way through, when things got difficult. Since it was an audio book I had to re-listen to passages two, three, sometimes four times before I felt like I could move on; the second half of the book is mind-blowing.

Tegmark maintains that we can no longer talk about the universe because it is believed that ours is only one universe out of an infinite number of universes, which is referred to as the multiverse. So far so good. But then the author starts talking about parallel universes.

There are at least five theories why a multiverse is possible, and Tegmark, pursues this line of thinking.

- No one knows what the shape of space-time is, but one prominent theory says that it is flat and goes on forever, which presents the possibility of there being many universes out there. But particles can only be put together in so many ways, which means that within infinity, things would have to start repeating.

- There is a theory of “eternal inflation” that says when looking at space-time as a whole some areas of space stop inflating, like how the Big Bang inflated our universe, but other areas of space will keep on inflating. This is visualized as a series of bubbles. We are in one bubble, but there may be another bubble just beyond ours that exists but is not connected to us. In this and other subsequent bubbles (universes) there may be laws of physics different than our own. Max Tegmark believes there are at least three levels of universes, but probably more.

- Following the laws of how subatomic particles behave (quantum mechanics) there would be a range of universes.

- Now we come to mathematical universes (which explains the title of Tegmark’s book, Our Mathematical Universe). The structure of mathematics may change depending on which universe you live in, and Tegmark says there is at least one purely mathematical universe “that can exist independently of me that would continue to exist even if there are no humans.”

- And finally, parallel universes: Going back to the flat conception of space-time, the number of possible particle configurations is limited to 10 to the 10th power to the 122nd power worth of possibilities. In an infinite space, with an infinite number of cosmic patches, the particle arrangements within them must repeat an infinite number of times. In this scenario there is a universe out there exactly like ours containing someone exactly like you.

Finally, let me leave you with one more thought, something that Einstein believed — that time is an illusion — it is just a very persistent illusion.

Thursday, July 24, 2020

I have been designing and installing public art for almost twenty years. I remember because my first and second public art projects were delayed and affected in different ways by the occurrence of 9/11. Security at the Seattle-Tacoma Int’l Airport had to be rethought and reconfigured, pushing back the installation schedule of the mosaic columns project from 2001 to 2004. The other project, at P.S. 58, a pre-K to 9th Grade school in Maspeth, Queens, was renamed The School of Heroes because Maspeth was the home of two Fire Stations, one of them a Haz-Mat Unit, that suffered big tolls in casualties on 9/11. My commission was to install painted panels in the Auditorium; I ended up using the two large panels on either side of the stage to depict scenes referring to 9/11.

I bring this up because I am a finalist for a project in New Jersey that has me doing something I have never done before. I have always known that my studio work and my commission work live in very different parts of my brain. They use different skills: the studio work — painting and drawing — is an intuitive, searching process where most of the time I do not know what I want or where I am going: I simply follow my nose. Because my work is so process-driven I start my paintings and drawings with almost no idea of what I want to do. All the thinking and planning occurs on the surface of the artwork. I add, sometimes I subtract, but the work is built overtime in layers.

The commissions are very different; they are designed with specific things in mind. For example, the budget is the first thing I consider because it determines what I can afford to do. Materials and fabrication costs vary greatly; anything that is handmade is expensive, whereas processes that can be machine made or programmed into a computer, are much more affordable. I am also guided by a site, a space, a size, and an anticipated audience. In the commissions I borrow from the visual vocabulary I have developed in my studio work. The fun of doing a commission is being able to translate my visual language into different materials, at times build them in monumental sizes, and I end up with a permanently installed artwork that lives in public.

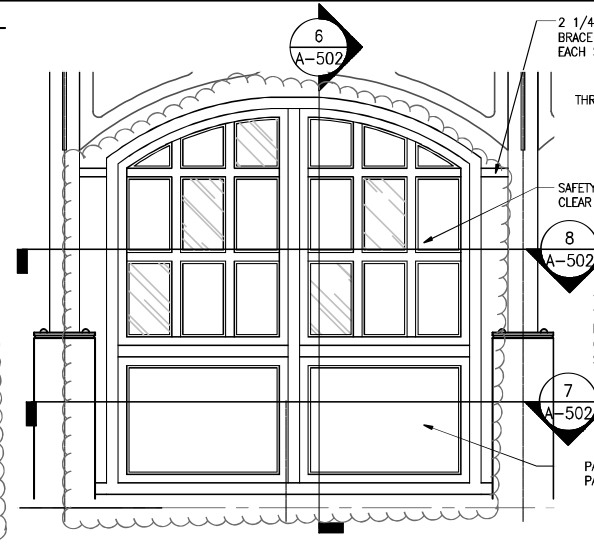

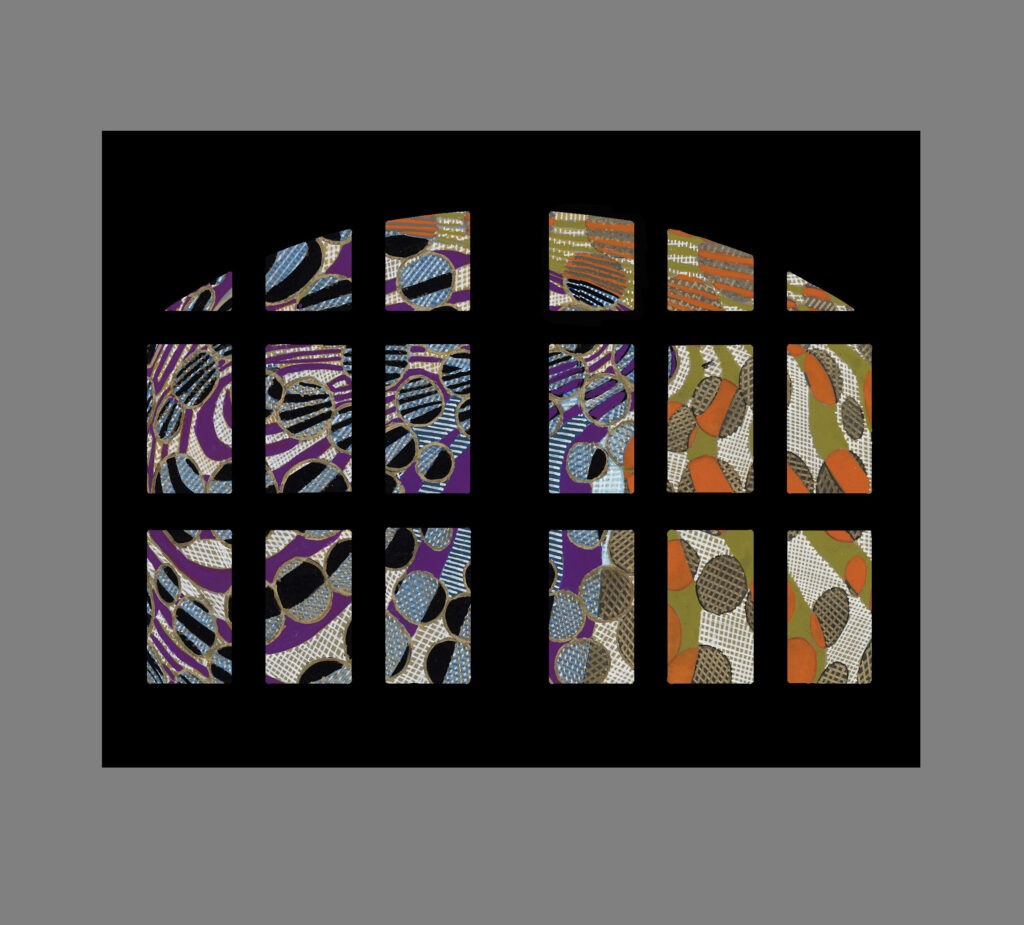

The New Jersey project involves designing laminated glass that will fit into windscreens like this drawing. Architecturally speaking, these are quite elaborate windscreens that look and feel like formal double doors or stately arched windows. But they are in fact what they claim to be, windscreens located in the open air at above ground train platforms.

I was quite intimidated when I first realized that this was the structure I had to design for. To have to consider how the arch and the partitions would affect a composition seemed complex and the notion that I had to come up with a total of seven designs in a month or less seemed overwhelming.

Then I got a bright idea. I decided to see what it would look like if I took some of my current gouache and oil marker drawings and inserted them in.

I quite liked the effect

Wednesday, July 15, 2020

I am going to address the development of my recent studio artwork. I knew by mid-2018 that the Mandala paintings I had been producing since 2011 had come to an end. When I was a young artist, the end of a series caused me great distress; I had a bad habit of wanting to hang on, to try and extend the life of a series. The trouble is that, as artists, we don’t have that much control over what we do — the artwork has a life and will of its own quite separate from the will of the artist. You know a series is at an end when the interest, excitement, sense of exploration is gone. Refusing to acknowledge this fact leaves you stuck in place, making weaker and weaker work.

Many Chamber, oil on canvas, 48” H x 72” W, 2015

This painting, Many Chambers, is for me a high point of the Mandala Series. The Mandala series, was my attempt to bridge — for lack of a better term — my conflicted ethnic identity. I knew that my visual aesthetics was rooted in Eastern Art, in the Middle Eastern and Far Eastern love of pattern and decoration; as opposed to Western Art and its roots in a Greco-Roman tradition that emphasizes the human figure and man’s centrality in the world. The Mandalas allowed me to use an iconic circle, or circles, within a rectangle that I could “decorate” to my heart’s content. In doing so I could draw as much as I wanted from Western art traditions. In Many Chambers, I added pearls, lace, and references to Medieval shields.

When I moved to New York City in January 2019, I was fortunate to have a three-month Artist Residency at the Carter Burden-Covello Center at E. 109th St. I spent months flailing in the studio trying out different mediums. Nothing worked until looking at architectural and perspectival diagrams, I got an urge to make linear compositions using oil markers, and traditional drafting tools like rulers, compasses, and trammel points.

North Star, oil and oil markers on canvas, 30 x 30”, 2019

The painting, North Star, is emblematic of the work I was making at the end of my three-month residency. What this transitional body of work made clear to me is that I absolutely did not want to rely on the use of symbols. I have relied on symbols in my work since forever. I was finally ready to admit to myself that I did not believe the symbols I have been using. In North Star I rely on the symbolic use of “the heavens” by employing a sky background and planet-like globes.

Untitled 2019-14, gouache, oil, oil markers on paper, 6 x 9 inches, 2019

It was in the following two months that the work in the studio cohered for me. I left off working on canvas and began to make small drawings with gouache, oil, and oil markers, which began rather mandala-like until they became more spatial.

Untitled 2019-22, gouache, oil, oil markers, 6.75 x 10 inches, 2019

Perhaps I need to explain the difference between “symbols” and “inferences.” The current work, although abstract, sometimes infers space, globes, sky, etc. but they are not symbolic because the artworks do not live or die depending on the “meaning” of any symbol. The artwork succeeds on its own terms — without relying on exterior meaning.

I came to perceive the 2019 drawings in the aggregate to be focused on the slow process of unveiling, recognizing, seeing, knowing and understanding.

They speak to the presentation of the self. People are complex, layered: we are comfortable with certain aspects of ourselves which we foreground or project outwardly; keeping in the distance, obscured, layered — aspects of ourselves that feel more tender, vulnerable, private. Perhaps because I am aware of this tendency in myself, I saw the layering, the veiling, as choices we make in what we reveal, how much, and when.

Alternately the drawings can be looked at as being about the time it takes to acquire knowledge, information, acquaintanceship. We are taken in by the large, bright, obvious aspects of people and things. Truly getting to know somebody or something is a slow process. We are often fooled by the presentation — people, after all, are known to lie to themselves; thus it takes time and we discover things in layers: it takes discernment and long exposure to perceive the deeper truths.

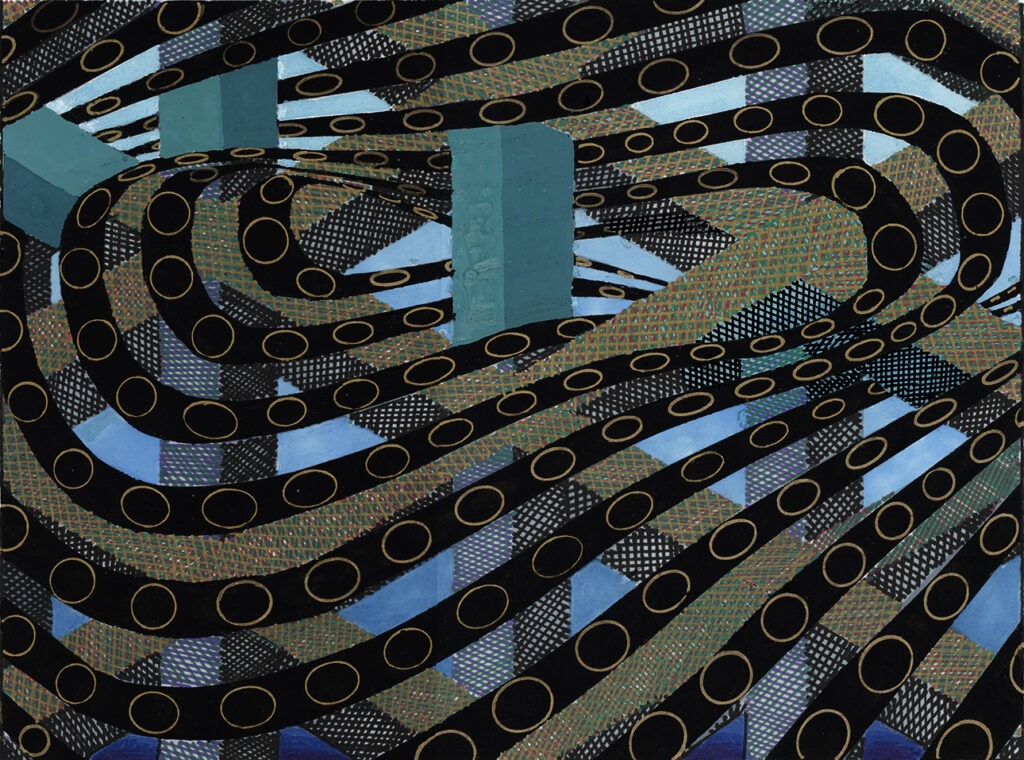

The drawings from 2020 are related to their predecessors yet seem different. I perceive a more concrete and focused presentation of the environment. Instead of being focused on objects in space, the specificity of each environment/situation dominates each picture.

Untitled 2020-06, gouache, oil markers on paper, 8.75″ H x 11.75″ W, 2020

It was not until this drawing, Untitled 2020-06, appeared that I began to read the series as focusing on navigation within constraints. We have to abide by the laws of nature and the laws of man; we are all socialized to live within society, to play by the rules. Although we live within guardrails, it is our job to navigate a personal way of going through life, of being in the world that gives us enough flexibility to be ourselves, to fulfill our needs, to accomplish our personal, or societal goals. I think these works reflect this particular aspect of the human condition — of the need to learn how to flourish within constraints.

Wednesday, July 8, 2020

The first (and only) blog I kept was in 2017 chronicling the months I spent in the Far East. I wrote the blog more or less as a record for myself since I didn’t expect anybody to read it, although I came to learn that many friends and family did.

My excuse for starting this blog is that in the midst of the pandemic, I spend a lot of time alone, and talk to few people. To break out of my isolation I decided to keep a weekly blog — that means one entry a week — nothing that will strain either me or my readers — should there be any…

To locate myself I took a selfie in front of my Upper West Side apartment building where the Cafe Luxembourg is located.

This is my subway, the W. 72nd St. 1/2/3 train station. Note how eerily empty the street is.

This is the exterior of my Brooklyn studio building, located near Graham Ave. on the L line.

My corner of the large studio I share with four other artists.

The messy table where I work on my gouache and oil marker drawings.